Why DC Microgrids Are Perfect for Your DIY Solar Setup

Updated:

Picture this: you’re running LED lights, a laptop, and a small fridge in your off-grid cabin, and every device is drawing power directly from your solar panels without converting DC to AC and back again. That’s the elegant simplicity of a DC microgrid system, where electricity flows in its natural solar form from panel to battery to device, eliminating the energy losses that plague traditional AC setups.

DC microgrids operate on the same direct current electricity your solar panels produce, typically at 12V, 24V, or 48V. Instead of converting that power to AC through an inverter (losing 10-15% in the process), then converting it back to DC inside your phone charger or laptop (losing another 10-20%), you skip the middleman entirely. For applications like RVs, boats, small cabins, or backup power systems, this approach delivers remarkable efficiency and simplicity.

The practical advantages extend beyond energy savings. DC systems reduce component costs since you’re not paying for expensive inverters. They’re quieter without the hum of AC conversion. They’re more reliable with fewer failure points. And they’re surprisingly expandable, you can start small with a single panel and battery, then grow your system as needs evolve.

The catch? Most household appliances run on AC power, so pure DC microgrids work best for specific applications rather than whole-home power. But if you’re powering a remote project, building an emergency backup system, or outfitting a mobile setup, understanding DC microgrids opens up cost-effective possibilities that traditional AC-first thinking overlooks completely.

What Makes a DC Microgrid Different (And Why You Should Care)

The Simple Truth About DC Power

Let me break this down in the simplest way possible. DC stands for Direct Current, and it’s electricity that flows in one direction, like water through a garden hose. Think about your phone charger. Your wall outlet delivers AC (Alternating Current), but that little brick on your charger converts it to DC because your phone’s battery can only store DC power.

Here’s something I realized years ago while camping: solar panels are DC machines by nature. When sunlight hits those photovoltaic cells, they produce DC electricity automatically. No conversion needed. It’s the same type of power your car battery uses, the same juice that runs your laptop when it’s unplugged.

This is actually huge for anyone thinking about solar. Every time you convert power from one form to another, you lose some energy as heat. It’s like pouring water between buckets – a little splashes out each time.

In my own workshop, I run several DC devices straight from my panels without any conversion, and the difference in efficiency is noticeable. Your portable cooler, LED lights, USB devices, and most battery-powered tools all want DC power anyway. They’ve just been living with converters their whole lives.

The beautiful simplicity of DC microgrids is that they skip unnecessary conversions. Solar panel produces DC, battery stores DC, device uses DC. It’s a straight line instead of a zigzag, which means more of your hard-earned solar power actually does useful work.

Where AC Systems Waste Your Energy

Here’s something I learned the hard way during my first solar setup: every time electricity changes form, you lose some of it. Think of it like pouring water between different-sized containers – a little spills each time.

Traditional AC solar systems have these conversion losses built right in. Your solar panels naturally produce DC power (that’s direct current, like what comes from a battery). But most homes run on AC power (alternating current, what comes from the wall outlet). So here’s the journey your solar electricity takes:

First, DC power from your panels travels to an inverter, which converts it to AC for your home. That conversion wastes about 5-10% right there. But wait – if you want to store energy in batteries (and who doesn’t want backup power?), the AC electricity then gets converted back to DC for battery storage. Another 5-10% loss. When you actually use that stored power, it converts from DC to AC again. You’re losing efficiency three times in one system.

I remember checking my friend’s solar setup and discovering he was losing nearly 25% of his generated power just shuffling electricity back and forth between AC and DC. That’s like filling your car’s gas tank but a quarter of it leaks out before you even drive anywhere.

These losses also generate heat, which can shorten equipment lifespan and create cooling challenges. It’s not just about wasted energy – it’s wasted money on equipment that works harder than necessary.

The Real Benefits of Going DC for Your Solar Project

Efficiency That Actually Shows Up on Your Power Meter

Here’s where things get really interesting – and measurable. When I switched my workshop over to a DC microgrid last year, I actually tracked the numbers with a power meter, and the results were eye-opening.

Traditional AC solar setups lose energy at every conversion point. Your solar panels generate DC power, which converts to AC through an inverter (losing 5-10% right there), then back to DC for devices like LED lights, phones, and laptops (another 10-15% loss). That’s potentially 25% of your solar harvest just vanishing as heat.

With a DC microgrid, you skip those conversions entirely. In real-world testing, most DIYers see efficiency improvements between 5-30%, depending on their specific setup and loads. For my 400-watt system, that translated to an extra 60 watts of usable power – enough to run my laptop for an additional three hours daily.

Here’s what this means practically: if you’re running a small off-grid cabin with a 1,000Wh battery bank, that 20% efficiency gain gives you an extra 200Wh daily. That’s the difference between having lights for four hours versus five, or running a 12V refrigerator continuously versus rationing power.

Battery life improves too. Fewer conversions mean less heat stress on your batteries, and you’re cycling them less deeply because you’re actually using more of what your panels generate. Several people in our community forum have reported their battery banks lasting 6-12 months longer than expected – that’s real money saved.

Simpler Wiring, Fewer Headaches

Here’s one of my favorite aspects of DC microgrids: the beautiful simplicity. When I first started building these systems, I was amazed at how much cleaner everything looked compared to traditional AC setups.

Think about it this way. In a typical AC system, you’re constantly converting electricity back and forth. Solar panels produce DC power, which gets inverted to AC, then your devices that need DC power convert it back again. Each conversion means more equipment, more wiring, more potential failure points, and more efficiency losses.

With a DC microgrid, you eliminate most of that dance. Your solar panels speak the same electrical language as your batteries and many of your devices. I remember working on a small cabin project where we powered LED lights, a DC refrigerator, and USB charging stations directly from the battery bank. The wiring diagram fit on a single page, and installation took half the time I’d budgeted.

For DIYers, this translates to fewer expensive components to purchase and fewer things that can go wrong. You’re not dealing with the complex synchronization requirements of grid-tied systems or multiple inverters scattered throughout your setup.

My tip? Start by identifying which of your loads can run on DC. You’ll be surprised how many modern devices already want DC power anyway.

Lower Costs When You Build Smart

Here’s where DC microgrids really shine in your wallet. When I first calculated the savings on my cabin setup, I was honestly surprised at how the numbers added up.

Traditional AC systems require inverters that can cost anywhere from $500 to $2,000 depending on your power needs. With a DC microgrid, you skip most of that expense entirely. Sure, you might still want a small inverter for those few AC devices, but we’re talking about a $150 unit instead of a massive one.

The real savings come from DC-native appliances. A 12V DC compressor fridge runs about $400-600, comparable to a quality AC fridge, but you’re eliminating the inverter cost and ongoing conversion losses. LED lighting is dirt cheap now, with 12V fixtures costing $10-30 each. Water pumps, fans, and phone chargers designed for DC operation are increasingly affordable too.

Let’s break down a basic system comparison. An AC setup might cost you $1,200 in inverters plus higher capacity batteries to handle conversion losses. The equivalent DC system? Maybe $300 for a small backup inverter and smaller battery banks since you’re not wasting 10-15% of your power in conversions. Over a small cabin installation, you could easily save $800-1,200 upfront while actually improving efficiency.

Perfect Use Cases for DC Microgrid Systems

Off-Grid Cabins and Tiny Homes

Here’s where DC microgrids really shine. I’ve visited several off-grid cabins over the years, and the ones running pure DC setups are beautifully simple and incredibly efficient. When you think about it, most modern cabin essentials already want DC power: LED lighting (12V or 24V), USB device charging, small fridges, water pumps, and fans. Why convert to AC and back again when you can skip that entire step?

A typical small cabin might run comfortably on a 24V DC system with 800-1200 watts of solar panels, a 400-800Ah battery bank, and a basic charge controller. Your lighting draws maybe 50-100 watts total, a DC fridge uses around 40-60 watts average, and a water pump cycles occasionally. Add your phones, tablets, and maybe a laptop, and you’re still under 200 watts most of the time.

The beauty here is simplicity. No inverter humming in the background wasting 10-15% of your power. No compatibility issues. Just direct, clean power flowing from your panels to your batteries to your devices. One builder I met in Colorado ran his entire 400-square-foot cabin for three years without a single AC outlet, and he never felt limited. The key is planning your loads around DC from the start rather than trying to retrofit an AC-designed space.

RVs, Vans, and Mobile Solar Setups

If you’ve ever gone camping in an RV or van with solar panels on the roof, congratulations—you’ve already used a DC microgrid! These mobile setups are probably the most common real-world example of DC microgrids in action, and they work beautifully because everything in your vehicle naturally runs on DC power.

Here’s why DC microgrids dominate the van life and RV world: your solar panels produce DC electricity, your batteries store DC electricity, and most of your gadgets either run directly on DC (LED lights, fans, USB chargers) or use small, efficient DC-to-DC converters. There’s no need for a big inverter humming away in the background, wasting energy and generating heat.

I’ve talked to countless weekend warriors who’ve installed their own RV solar setups without realizing they were building miniature DC microgrids. They just knew it made sense to wire their panels directly to a charge controller, then to batteries, then to their lights and phone chargers. That intuitive simplicity is the beauty of DC systems.

The efficiency gains really matter when you’re boondocking for days without shore power. Every watt counts when you’re trying to keep your fridge cold and your devices charged. Plus, DC systems are safer in the confined, moving environment of a vehicle—lower fire risk and simpler troubleshooting when you’re miles from the nearest mechanic.

Backup Power and Emergency Systems

One of the most practical reasons I recommend DC microgrids to folks just getting started is their reliability during power outages. Think of it as your home’s safety net. When the grid goes down, a well-designed DC microgrid can keep your essential circuits running without the complexity and losses of converting back and forth between DC and AC.

Here’s how it works in practice: You identify your critical loads, the stuff you absolutely need during an emergency. That might be your refrigerator, a few LED lights, phone chargers, and maybe a small medical device. By running these on a dedicated DC circuit connected to your battery bank and solar panels, you create an independent power island that operates regardless of what’s happening with the utility grid.

I’ve seen homeowners set up simple systems with just a few solar panels, a charge controller, and a modest battery bank that can run essential circuits for days during outages. The beauty is that sunlight keeps recharging your batteries, extending your backup power indefinitely in sunny conditions. You’re not dependent on gasoline for a generator or waiting for grid repairs.

For maximum reliability, keep your emergency DC circuits separate from your main household wiring, clearly labeled and dedicated to those critical devices you’ve identified.

Key Components You’ll Need (Without Overcomplicating It)

Solar Panels and Charge Controllers

Solar panels and charge controllers are the dynamic duo of your DC microgrid. Here’s how they work together: your solar panels generate DC electricity when sunlight hits them, and the charge controller acts as the smart traffic cop, regulating that power before it reaches your battery bank. Without a charge controller, you’d risk overcharging your batteries, which can seriously damage them or reduce their lifespan.

The key to success is matching voltages across your system. If you’re running a 12V system, you’ll want 12V panels (or panels wired to output 12V) and a 12V charge controller. Same logic applies for 24V or 48V systems. I’ve learned from working on various off-grid solar installations that mismatched voltages are one of the most common beginner mistakes.

Sizing matters too. Your charge controller needs to handle the maximum current your panels can produce. We’ve created calculator tools on our site specifically for this purpose—they’ll help you determine the right controller size based on your panel wattage and system voltage, taking the guesswork out of the equation.

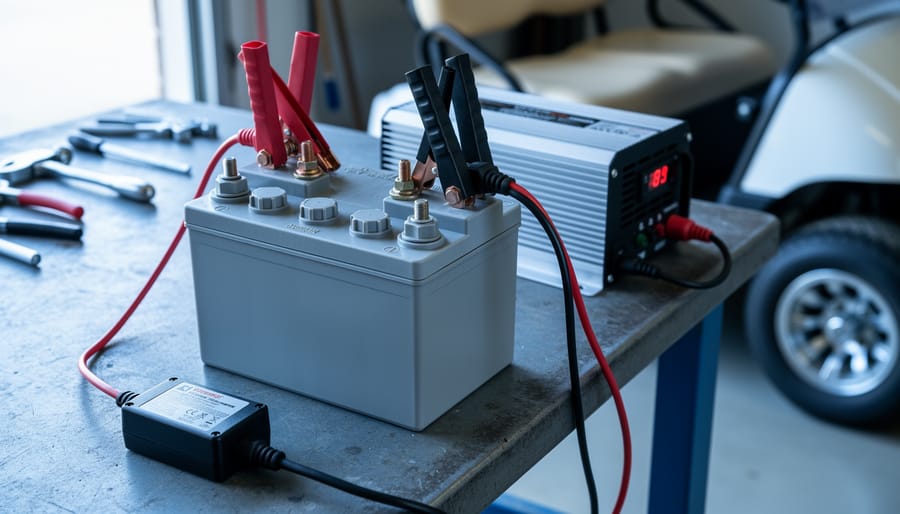

Battery Banks: Your System’s Heart

Think of your battery bank as the heart of your DC microgrid. It stores all that solar energy you’re collecting during the day and keeps everything running when the sun goes down or hides behind clouds.

When I first built my off-grid cabin system, I went with flooded lead-acid batteries because they were affordable. They worked great, but required monthly maintenance and needed proper ventilation. These days, I’d probably choose lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries instead. Yes, they cost more upfront, but they last three times longer, require zero maintenance, and handle deeper discharges without damage. For weekend warriors or occasional users, sealed lead-acid batteries offer a middle ground with decent performance and no maintenance hassles.

Voltage selection matters more than you might think. Most small systems run on 12V because that’s what RVs and boats use, making components easy to find. But here’s the thing: if you’re powering anything beyond basic lighting and phone charging, consider stepping up to 24V or even 48V. Higher voltages mean lower current, which translates to thinner, cheaper wiring and less energy lost as heat. My rule of thumb? Stick with 12V for systems under 1000 watts, 24V for 1000-3000 watts, and 48V for anything larger.

For sizing, calculate your daily energy use in watt-hours, then multiply by two or three to account for cloudy days. This gives you a comfortable buffer without breaking the bank.

DC Distribution and Protection

Once you’ve got your DC power sorted with proper microgrid battery requirements, you need to distribute it safely. Think of your DC distribution panel as the traffic controller for your electricity—it directs power where it needs to go while keeping everything protected.

DC circuit breakers are your first line of defense. Unlike regular household AC breakers, DC breakers are specifically designed to handle direct current, which doesn’t naturally “zero out” like AC does. This makes interrupting DC current trickier, so never substitute an AC breaker in a DC system.

Fuses work as backup protection—they’re simple, reliable, and inexpensive. I always recommend fusing both positive and negative lines close to your battery bank. If something shorts out, the fuse blows instantly, protecting your equipment and preventing fires.

Your distribution panel should be clearly labeled and easily accessible. Mount it in a dry location away from flammable materials. Include a main disconnect switch so you can shut everything down quickly if needed. Good wire sizing matters too—undersized wires generate heat and create fire hazards. Use proper DC-rated components throughout, and don’t mix and match parts from different voltage systems.

When You Need AC: Hybrid DC Microgrid Approaches

DC-Native Appliances and Devices

You might be surprised how many everyday devices already prefer DC power! Most modern electronics—laptops, phones, tablets, and portable speakers—run on DC internally, which is why they have those bulky adapter blocks that convert AC from your wall outlet. In a DC microgrid, you skip that conversion step entirely, plugging these devices directly into your system with the right voltage.

LED lighting is perhaps the best DC application. DC-powered LED strips and bulbs are incredibly efficient and widely available in 12V or 24V options. I’ve installed them throughout my workshop, and the energy savings compared to my old AC setup are remarkable.

DC refrigerators and freezers, originally designed for RVs and boats, are game-changers for off-grid living. They’re more expensive upfront than AC models, but their efficiency makes them worth considering. Fans, water pumps, and even some power tools now come in DC versions.

What typically needs AC? Most kitchen appliances (microwaves, blenders, coffee makers), traditional refrigerators, power tools, and anything with a standard three-prong plug. Hair dryers, space heaters, and air conditioners draw significant power and almost always require AC through an inverter.

Finding DC appliances is easier than ever. Check marine and RV supply stores, off-grid specialty retailers, and online marketplaces. Search specifically for “12V” or “24V” versions of what you need.

Using Small Inverters Where You Need Them

Here’s the smart approach I’ve learned from building hybrid systems: you don’t need to convert your entire DC microgrid to AC. Instead, place small inverters right where you need them.

For example, I keep my refrigerator on a dedicated 300-watt inverter mounted nearby, while my lights and phone chargers run directly on DC. My power tools? They get a separate 1000-watt inverter in the workshop. This modular strategy means each inverter only runs when that specific device needs power, dramatically reducing idle losses.

Think of it like having multiple small generators instead of one giant one running constantly. When my fridge cycles off, that inverter isn’t wasting energy. Meanwhile, my DC circuits hum along efficiently for everything else.

This approach pairs beautifully with proper battery system selection, since you’re not oversizing your battery bank to handle massive inverter draws. Start by listing your actual AC needs. Most folks discover they only need AC for three or four devices. Mount appropriately sized inverters near those loads, keep your DC backbone strong, and enjoy the best of both worlds without the complexity or cost of whole-system conversion.

Getting Started: Your First DC Microgrid Project

Start Small: A Basic DC Lighting Circuit

When I first started exploring DC microgrids, I didn’t dive straight into a whole-house system. Instead, I built something small and manageable: a simple circuit to power a few LED lights from a solar panel. This project taught me the fundamentals without the risk of expensive mistakes, and I recommend every beginner start here.

Here’s what you’ll need: a small 20-50 watt solar panel, a basic charge controller (a 10-amp PWM model works great), a 12-volt deep cycle battery (even a small 20Ah battery will do), some DC LED strip lights or 12-volt LED bulbs, and basic wiring with inline fuses for safety.

The setup is straightforward. Connect your solar panel to the charge controller’s solar input terminals, respecting polarity. Then connect your battery to the charge controller’s battery terminals. Finally, wire your LED lights to the load terminals on the charge controller. Most charge controllers have built-in load management, which means they’ll automatically disconnect your lights if the battery gets too low, protecting your investment.

What I love about this project is how quickly you see results. Within minutes of sunlight hitting your panel, you’re generating power and charging your battery. By evening, you can flip a switch and illuminate your lights using energy you harvested yourself. It’s incredibly satisfying and gives you hands-on experience with voltage, current flow, and energy storage.

This simple system can light a shed, power camping trips, or serve as emergency backup lighting. Once you’ve mastered these basics, scaling up becomes much less intimidating.

Planning Your System Expansion

When I first built my DC microgrid, I made the classic mistake of buying just enough capacity for my immediate needs. Six months later, I was shopping for new components because I’d added a few more devices. Learn from my experience and think ahead.

Start by listing everything you might want to power in the next two to three years, not just today. Planning for 25-50% more capacity than your current needs gives you breathing room without breaking the bank upfront. Choose a charge controller that can handle additional solar panels, and make sure your battery bank has room for expansion. Modular systems are your friend here, batteries that can be connected in parallel are much easier to scale than replacing an entire unit.

The biggest beginner mistake? Undersizing wire and connections. If you install proper gauge wiring from the start, adding capacity later becomes straightforward. I recommend using our online solar calculator to map out different growth scenarios. It’ll show you how adding panels or batteries affects your system’s performance.

Another pro tip: document everything. Keep a simple diagram of your connections and a log of what components you have. Future you will be incredibly grateful when it’s time to expand.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Voltage Drop and Wire Sizing

Here’s something I learned the hard way during my first solar setup: DC systems lose more voltage over distance than most people expect. When I ran a 12V line from my solar panels to my battery bank using what I thought was adequate wire, I was shocked to discover I was losing nearly 2 volts along the way. That’s a huge chunk of power just disappearing into heat.

The issue with DC is that lower voltages require higher current to deliver the same power. Remember, watts equal volts times amps. So a 12V system carrying 10 amps delivers 120 watts, but requires much thicker wire than a 120V system carrying 1 amp for the same power. Higher current means more resistance loss, which is why DC microgrids need beefier wiring.

Here’s a practical rule: keep voltage drop under 3 percent for most applications, or 1 percent for sensitive electronics. To calculate wire size, you’ll need three numbers: current in amps, wire length (round trip, so double your distance), and acceptable voltage drop.

As a quick reference, for 12V systems running 10 amps over 10 feet, use 14 AWG minimum. For 20 amps, jump to 10 AWG. At 50 amps, you’re looking at 4 AWG or larger. Online wire gauge calculators make this math painless, and I’d recommend keeping one bookmarked on your phone for planning trips to the hardware store.

Safety Considerations for DC Systems

DC systems are incredibly safe when built with respect and basic precautions. I learned this early in my solar journey after a friend experienced a minor arc flash scare that could have been avoided with proper fusing.

The main concern with DC circuits is that arcs can sustain themselves longer than AC arcs, making proper protection essential. Always use DC-rated fuses or breakers, never AC-only components. They’re designed differently and it matters. Install fuses close to your battery bank, ideally within 7 inches of the positive terminal, to protect against short circuits.

Grounding is simpler in DC systems than most people think. For standalone systems like camping setups or small cabins, you typically need just a chassis ground connecting all metal enclosures. For large-scale off-grid power, consult local codes about earth grounding requirements.

My golden rule: never work on live DC circuits above 50 volts. Disconnect everything first. Use insulated tools, cover exposed terminals with electrical tape, and double-check connections before powering up. These straightforward practices keep your project safe and enjoyable.

Building your own DC microgrid might seem daunting at first, but here’s what I’ve learned after years of working with solar systems: you don’t need to do everything at once. Start with something simple, maybe a small DC lighting circuit for your shed or a charging station for your portable devices. Once you see how straightforward DC power can be, you’ll gain the confidence to expand from there.

The beauty of DC microgrids is that they meet you where you are. Whether you’re powering a weekend cabin, building an emergency backup system, or just want to reduce your electricity bills, there’s a DC solution that fits your situation and budget. The efficiency gains alone, especially when you’re working with batteries and LED lights, make DC worth serious consideration for anyone getting started with solar.

Remember, you’re not alone in this journey. Our community is full of people who started exactly where you are now, asking the same questions and learning through trial and error. I encourage you to explore the solar calculators and guides available here on the site. They’ll help you size your system properly and avoid the mistakes I made when I was starting out.

Don’t hesitate to reach out through our community forums either. Share your plans, ask questions, and learn from others who’ve walked this path before you. The solar DIY community is incredibly supportive, and there’s always someone willing to help troubleshoot or offer advice. Your DC microgrid adventure starts with that first panel and battery. Why not begin today?